About the Author

Claude Lewenz is by training a historian, by profession a serial entrepreneur who began in the computer industry back when software was still spelled with a dash in the middle. He did his government service working in what was said to be the third poorest city in the United States where, despite the grinding poverty of the rural American South, he found a much stronger sense of community than in more privileged society. There was something deeply wrong with how contemporary communities were being designed and inhabited. It was as if people were viewed as nothing more than fodder for developers and all the other vested industries associated with building places.

In 1995, he was given a book by a Māori architectural designer he had met, in of all places, a castle in Slovenia; a book by Victor Papanek that put that discomfort into words.

We all sense that something has gone terribly wrong with our communities. Hamlets and cities, slums and suburbs, all lack a sense of cohesion. Not only is there no centre there – there is no there there. Cities, towns, villages and communities that were designed hundreds of years ago are obviously based upon some basic purpose of living that eludes the designers of our own time. … Modern designers, whose purpose is the nourishing of public taste, have tried desperately hard – and with little success – to find out what that taste is. To help in this quandary, the designer uses research, staffs and questionnaires, and what does he discover when at last his work is complete? That those for whom he has built move back to the old quarters of the city.

So Claude began his own research. Rather than read books or ask experts, he travelled the world with a notebook and camera, looking for living patterns that he could see, hear and feel; human-scaled patterns that were wonderful – some best kept secrets, others places visited by millions because they are so wonderful. Some were found in New Zealand, most notably among tangata whenua in some of NZ’s more remote regions. The most were found in Old Europe where ancient, narrow streets necessarily kept out cars. As Papanek observed, the old quarters were designed with different values – not the sort of values derived from a workshop, but deeply embedded into human DNA.

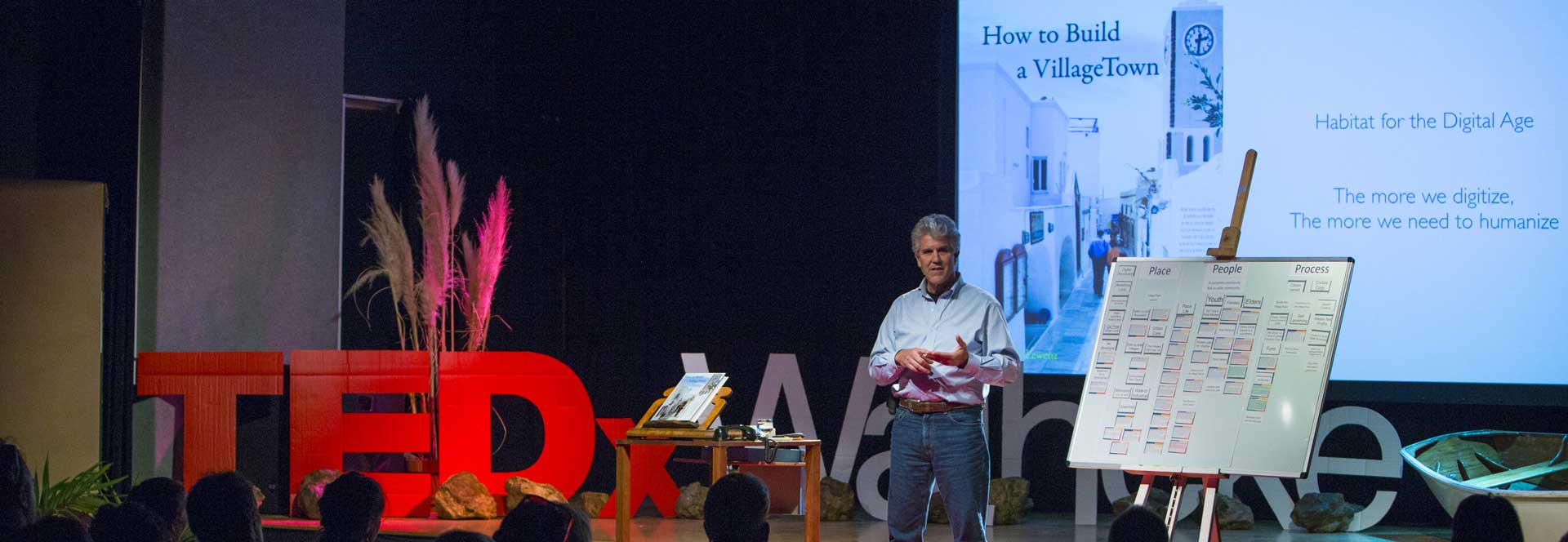

He took a lot of photographs, like the one on the cover of his book: a 2-metre wide main street in a town in Greece that has a million visitors a year using it. Imagine trying to get that by Resource Consent officials in New Zealand. Out of that research came a book and a lot of interest. But the timing was not right. Perhaps in 2023 its time has come.